Performance and Spectacle

Representations of African Americans included spectacular and theatrical representations in postbellum America. Minstrel shows, variety shows, theatre performances, and film expressed derogatory racial stereotypes to promulgate the idea of white supremacy.

Minstrelsy and Cakewalks

The 1901 Pan-American Exhibition in Buffalo, New York recreated the antebellum South in its exhibit called “Old Plantation.” Over 150 black performers were trained in minstrelsy and the cakewalk. The World’s Fair exhibits (an amalgam of Disney's Epcot Center, natural history museums, and zoological attractions) fused education and entertainment for millions of visitors. Two newspapers of the time period from Buffalo indicate the possible presence of a “minstrelsy school,” in which African Americans were “taught” how to represent black culture. The purpose of this school, like the purpose of many blackface productions, was to paint the South in a positive light and represent slavery as beneficial to society. Despite or because of this racist historical revisionism, minstrel shows increased in popularity, becoming a staple of idealized reproductions of the antebellum South.

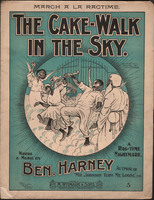

Cakewalk performance originated around the 1840s, when slaves parodied the ballroom dancing of the white slaveowners, strutting around the plantation grounds in their finest clothes (Fig. 2), sometimes on the lawn of the plantation house while the white slavelowners danced inside. Some cakewalks involved dancers placing pails of water on their heads, with a prize, usually a cake, awarded to the person who spilled the least water.

While black performers viewed their parody of plantation manners to be an insult to their white masters, the masters believed it to be splendid entertainment, resulting in an increase in the dance's popularity. Cakewalks, originally competitions among slaves on a single plantation, grew to include competitions between plantations (and their respective slaveowners). By the late 1800s and early 1900s, the cakewalk was incorporated into minstrel shows being performed across the nation, thereby perpetuating derogatory images of blackness and lampooning African American culture. What began as a satiric performance, in which black slaves mocked the snobbery and haughty attitudes of white slave-owners, soon became a caricature of black culture, with white men in blackface mocking the black originators.

While cakewalks began with African Americans ridiculing whites, minstrelsy, which also preceded the Civil War, was a performance of blackness by white actors--that is, white actors in blackface makeup performing in ways that illustrated whites' perceptions of black lives and cultures.

Minstrel performances marginalized their black subjects through the creation and perpetuation of characteristics that negatively represented African American appearance and behavior: a pitch-black face, exaggerated lips, and an animalistic nature. Minstrel shows, like the “Old Plantation” show at the Pan-American Exhibition, gave white audiences (the majority of whom were Northerners) an opportunity to gloss over the horrors of slavery by depicting the South in a nostalgic light. Shows such as these helped represent loyal slaves as “good Negroes,” while those who fought for African American rights were depicted as disruptive and threatening. The shows served as a way to culturally cover up the horrors of slavery and to paint American history in a less barbaric light.

Jim Crow and Zip Coon

A number of stereotypical figures were common in early minstrel shows. Jim Crow, a figure later associated with segregation, was commonly played by a white man known as “Daddy Rice.” Reportedly, Rice sported tattered clothes and blackened his face with burnt cork, making his skin “as black as a crow.” Ricevportrayed Jim Crow as “grotesquely twisted,” which allowed him to objectify African Americans as monstrous. Acting as Jim Crow served as a way for Rice to portray slaves as carefree, happy, comfortable, and even benefitting from their bondage. Sheila Reed, a writer for the Pensacola News Journal, indicates that after the birth of the character Jim Crow in the 1830’s, the terms “Jim Crow” and “Negro” eventually became interchangeable, which led to calling segregation legislation "Jim Crow laws" (See the "Laws and Race" page for more information on Jim Crow laws).

Often, blackface minstrel shows featured a component in which Jim Crow’s “Northern,” free cousin would appear, illustrating African Americans’ “devastating ways” toward white women. During this time period, African Americans were depicted as a danger to white women; such anxieties are evident in minstrelsy, Jim Crow laws, popular literature, and D.W. Griffith’s film Birth of a Nation.

“Zip Coon” was another stereotypical figure, described as a “free man." His name is an obvious reference to “raccoon,” illustrating the popular association of blackness with animality. The character's name shows dehumanization on the part of the white actors. Coupled with the animalistic portrayals of African Americans, minstrel shows often featured interpretations of what black “dialect” sounded like to white ears; rather than realistic portrayals, however, these dialectical “imitations” often showed a perceived intellectual incompetence. That is, through the rendering of black dialect on stage, white interpretations reflected black “stupidity,” further adding to the public perceptions of African Americans as animalistic, dangerous, or downright stupid.

Throughout the 20th century, however, minstrelsy was also increasingly performed by black actors, and some argue that minstrelsy, while having its roots in racism, actually paved an avenue for African American self-advancement in acting. With the increase in minstrelsy performed by black actors, African Americans were afforded possibilities to subtly criticize society in ways that they otherwise could not. For instance, as scholar Amma Kootin points out, in the “Old Plantation” show, there were two directors on stage: one white and one black, which suggests that the black actors may have been able to perform their own interpretations of their cultural dances, rather than doing a dance that was choreographed for them by whites. In other words, through minstrelsy, African Americans were able to subtly rebel, and contrary to white perceptions, were not merely willing participants in anti-black racism.

Spirituals, Illustrations, and Film

Like the original motivation for the cakewalk, music was a vital form of self-expression and aesthetic progress for African Americans in the late nineteenth century. As African Americans began to build new lives for themselves after being freed from the bonds of slavery, one of the tools they used to fuel their progress was music. Such practical use of music can be seen in choirs from Hampton University and Fisk University. Both of these schools had groups that traveled in the North, performing choral arrangements of spirituals to raise money for their institutions. The Fisk University’s Jubilee Singers even appear in Pauline Hopkins’ novel Of One Blood. As traveling groups increased exposure to and popularized spirituals, some African American spirituals were interwoven into Broadway musical revues; however, their undeniable meaning as religious pieces made them stand out, causing protest among white and black audiences alike.

Filmmakers at the time also relied heavily on performance to convey racial identity. Through makeup, exaggerated gestures and postures, and the movement of the body, white actors attempted to portray members of another race. Through these portrayals, racist stock characters representing perceived negative characteristics of African Americans were popularized: the mammy, Uncle Tom, the buck, the wench, the mulatto, and the pickaninny. These stereotypes were constructed early on in minstrel shows and vaudeville and continued to be popular throughout the early years of film history.

In contrast with the commonplace practice of whites in blackface, early films by African Americans offered more diverse representations of black culture. Though few and far between, these films utilized all African American casts and were shot and edited by African American crews. The companies would often remake popular white films in order to feature black actors and to reach out to black audiences. Unfortunately, these films were shown only in small African American theatres. Four production companies circulated the majority of these pictures: The Ebony Film Company out of Chicago, The Lincoln Motion Picture Company, The Micheaux Book & Film Company, and Norman Film Manufacturing Company in Jacksonville, Florida. Oscar Michaeux would go on to direct over 40 films to become the head of the most successful African American production company of the time.

Echoing the covers of nickel weekly magazines (Fig. 5 and 8), the silent films of the period also contained images of racial representation that relied heavily upon white characterizations of African Americans. Building on traditions of blackface minstrelsy, white actors often used thick makeup and grease in order to mask their whiteness and portray characters of other races. D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915) is perhaps the most famous and controversial of these films. Casting a heroic light of the members of the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction, the film attempts to show the monstrous nature of the African American. The contrast of actress Lillian Gish's ivory skin with the dark makeup of the actors in blackface further accentuated the racial divide of the film.

In the adventure films of the period, black characters were rarely given any key roles within the narratives; instead, they were relegated to the roles of sidekicks or tribesmen. Such stereotyped roles were typically played by white actors in blackface. Films like Scott Sidney's Tarzan of the Apes (1918) did cast African Americans as tribal Africans, but showed them as nothing more than oddities, compared to the regal Jane and her fellow white companions.