Blackness in Art and Music

This page specifically examines aspects of sheet music covers, cakewalk, and film and their representations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Artwork and illustrations of this period commonly featured crude stereotypes of African Americans.

African American Spirituals

African American spirituals had their roots in slavery. These songs, many of which were about hope for the future, provided an outlet for slaves to practice their faith, and in doing so, stay focused on a future without slavery, even if that was to be in the afterlife. As slaves were freed, and future generations looked for ways to preserve this music, it became evident that certain aspects of these spirituals could not be captured by the musical notations available in Western culture. The earliest spirituals were born out of feeling, and the previously mentioned musical notations were not perfectly able to carry this. Additionally, these spirituals were often performed with variations, both great and small, so to try and confine them to a single setting in sheet music proved a struggle.

Some early texts were created to try and capture much of the depth of spirituals, but much was lost in translation. As many of these spirituals originated on the plantations, they were first sung a cappella, without instruments. When the songs were adapted for sheet music, the earliest forms were either a cappella or had simple instrumentation. This simple instrumentation can be seen in pieces from “Ten Negro Spirituals,” an early collection of spirituals in sheet music form. These songs are for solo voice with piano. Such a collection would have been available for personal use. Included in this exhibit are two pieces form this collection, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “Ride On, King Jesus” (Fig. 11). An examination of the lyrics of these pieces reveals that while they were melodically simple, and often lyrically repetitive, they were very much based in religious faith. A recording of "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" recorded by the Fisk University Jubilee Quartet can be found here. This quartet was part of the larger two-quartet chorus, the Jubilee Singers. This group was created shortly after the founding of Fisk University to help raise funds for the college, which was struggling financially. The group toured throughout the northern states, and is still in existence today.

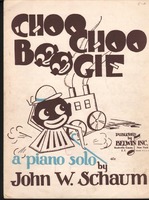

Cover illustrations for the sheet music of spirituals frequently misrepresented the character of the music. Illustrations were typically dominated by caricatured, blackface tropes: bulging eyes, large lips, watermelons, patchwork clothing, and other stereotyped markers of blackness. Sheet music for minstrel songs included similar images, featuring white performers, typically men, with their faces painted in standard blackface style: all black except for the area around the mouth and eyes, which were left bare to create the illusion of comically large lips and eyes (Fig. 12). Some pieces, such as "Choo Choo Boogie" (Fig. 1), also used these stereotypes to literally objectify blackness in their illustrations, reflecting the continued perceived inferiority of African American people and culture.

Cakewalks

The cakewalk began as a way for African American slaves to secretly express themselves through dance. The appropriation of the cakewalk by different cultures may have altered the way in which the dance was interpreted, but syncopated music was a key feature of the cakewalk until the 1940s. (Syncopation occurs when the normally unaccented beats in music are stressed.) The music of the African American cakewalk went on to inspire other popular music of the 20th century, and eventually gave birth to ragtime music, another African American music genre. Musically, ragtime was a bit more complicated than the cakewalk, and syncopation was not as prevalent. Cakewalk and ragtime music strongly influenced composers such as John Phillip Sousa, and eventually found its way to Broadway productions and became fashionable in upper-class society.

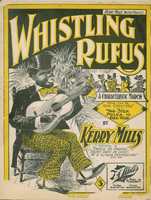

The first million dollar-selling cakewalk, "At a Georgia Campmeeting" (Fig. 5), was written by Kerry Mills, a leading composer. Mills’ success refuted white perceptions of blacks as incapable or less intelligent, instead demonstrating the ability of African Americans to represent themselves artistically and culturally.

As a result of their growing popularity, cakewalks were also frequently depicted in art. Now a national phenomenon, the performance of cakewalks became a stereotypical and caricatured image of black people. Stereo cards, photographs, lithographs produced by famed printer Currier and Ives, sheet music covers, advertisements for Arm & Hammer Baking Soda, and even a board game, The Cakewalk Game, tried to capture the performance of cakewalks to sell to American consumers.

These images often included racial stereotypes of black people (Figs. 2 and 5). Notice in Smoky Mokes (Fig. 10) that the sheet music cover depicts a photograph of four African American children smiling for the camera; this is the only photograph of African Americans on the sheet music covers in this collection. One example that does not include stereotyped and racialized portrayals of African Americans is the sheet music cover of the Edgecombe Cake Walk (Fig. 6). The sheet music, which was published in Cincinnati, OH features elaborate red lettering and intricate designs in lieu of any racial depictions.